Fiction: Jean-Michel François, Part 1

“You ever read the news? A pound of butter’s 2 bucks yesterday, 4 today. You think that’s just God or bad luck? Please.”

There was an envelope on his desk when Jean-Michel François came back from lunch, green with a little plastic window in the top right corner, LEGAT PR 0593 - NOT FOR DISSEMINATION showing in red type.

On a teal post-it, written in a decoish script: Delestrez says this one’s for you.

He peeled the note off and threw it into the garbage, turned the envelope over several times, weighing its contents, then leaned as far back as his chair would go and tore the thing open.

A notice from the FBI. French national under investigation: Pierre Choucair, xx/xx/76, aerodynamics engineer at Nantex-Marechal SLR. French and Lebanese passports.

Motive: Because of an ongoing inquiry, we cannot at this time divulge the FBI’s interest in Mr. Choucair.

Further requests: Any and all information obtained during any and all previous or ongoing investigations of Mr. Choucair, including but not limited to and then a two page list: train trips, plane trips, phone calls, domestic banking, medical records, SWIFT. Everything, in other words.

He double-clicked on the National Police icon on his desktop, logged in, put Choucair’s details into inquiries. NO RESULTS FOUND.

Back on to the desktop, réponse formulaire.doc. Under FRANÇOIS, JEAN-MICHEL, MAJOR DE POLICE À L’ÉCHELON EXCEPTIONEL; BUREAU D’INTERCOOPERATION; AGENCE DE COORDINATION; POLICE NATIONALE; RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE and some opening formalities, he wrote in English:

We regret to inform that the National Police has no interest now or ever in M. PIERRE CHOUCAIR at this time.

Hit print, made a note in a ledger he kept in the drawer of his desk. Then he put the file in a carousel marked DONE.

Staff meeting in 20. Did he have time to bother Delestrez? No good being pushy, but still, he had said there’d be word this week….

He let his eyes wander round the low margin of office beneath its overcast ceiling. Post-lunch loitering; the older guys, lifers, in a pleasant torpor of digestion; the young ones already on the phone still sure they could talk their way out of here.

At the far end of the room were three closed doors, dignified by their remove, gold plaque on each set with slim caps: CAPITAINE LAMBERT, CAPITAINE JACQUET, and the largest, right corner all to itself, COMMANDANT DELESTREZ.

And Jacquet’s just sitting there, empty.

Jean-Michel François looked at each of his colleagues in turn and wondered, as he had done for weeks, which one was trying to steal his promotion.

His phone dinged. He glanced over—and turned it face down. Then he got up and went the long way around to the printers to find his letter.

It was dark and pissing by the time he left. A quarter of an hour earlier he’d finally tried cornering Delestrez. A genteel man of sixty, three beautiful children and a very charming wife, a hundred and fifty square meters in Paris and two hundred and fifty more of beachfront in the Landes, the commandant was a man who lived in a state of perpetual mourning. “Nothing yet, I’m afraid. I can say that no other candidates have been added, but—” He’d sucked his teeth. “It’s very political, this, Jean-Michel. Very political….”

It pissed gently but merrily on Jean-Michel François all the way along the low-slung, yellow-brick, two-story, terracotta-roofed, Chinese-warehouse-and-Islamic-cultural-club, barbed-wire walk to the train station.

A gang of teenagers crowded the road two blocks away, pushing and being pushed, laughing when pushing, lashing out—"FUCK yo,” “The fuck’s your problem,” “Yo— Listen to this baby crying,” “Faggot”—if pushed. They went quiet as he passed, watching from under their hoods.

He kept his left hand in his pocket, thumb on the three stripes adorning the little tin shield, and his right on the holster of his gun, until he was down the block. At the corner, he heard jeers behind him, looked back and saw the kids turn away quickly, making like they were kicking round an invisible ball. He stared at them until they drifted off sulkily.

It was past 10 when he got home. Camille was still awake. “It was hard to get Lucie to sleep,” she said, not looking up from texting. “So be quiet when you go to the bathroom.”

He'd been in bed for ten minutes when his wife put her phone down, got up to close the door, pulled off her pajama bottoms, and got back under the covers. “It's not for a week, but they say it's important to have some in there before, to maximize the chance of it getting to the egg.” He was tired, but what was there to complain about really. It was for a good reason.

He put out the light. She made her noises: “Hmm, hmm.” He finished.

They lay together afterwards, Camille on his chest. “Then she just started crying. It was like she wanted to tell me something, but all she said when I asked was that they’d been arguing a lot lately. I don’t know why, but I felt like she was going to admit to something, something big, really big, something like, well—”

“Like what?”

He knew Camille was frowning even without looking at her: that little upside-down vee like a stitch in her brow. “Like she was having an affair,” she said.

Then she asked: “Do you think Cécile could do something like that?”

He said you never knew with anyone, not even your family. That was what you learned being in the police. “The truth isn’t what you think it should be.”

Then, because it was dark, they rolled over and went to sleep.

Though actually he lay there for a few minutes longer, feeling what he had often felt before, that, when all was said and done, his was the right kind of life.

“’Scuse me.”

Jean-Michel François was in the lobby of the Hotel Central Parc in Brussels having a coffee at the café bar. Across from him, next to a pair of double doors marked Salle de conference, hung a banner: Transnational Policing: Intercooperative and Collaborative Approaches. An easel underneath it read: Next up: Cooperation: Dos and Don'ts.

A man stood beside him hand out when he turned. “Vecco,” the man said. “FBI.” He had a high fade combed from left to right and drenched in pomade. His face was fat the way a child's was, though he had to be at least forty years old.

They shook hands, and Jean-Michel François introduced himself. “French police?” Vecco said. “That’s funny.” But it wasn't clear what the joke was.

Vecco was here for the conference, he explained. He'd been overseas for a while. “Embassy detail first. Kuwait, Cartagena, Tel Aviv.” As for the FBI: “Love it. Just absolutely love it. It’s my speed. I’m a meat-and-potatoes guy, you get me? Good guys and bad guys. Black hat and white.”

His suit fit him like a surgical bandage. His shoulders had to have been nearly an inch beyond the seams. He also towered over Jean-Michel François, who didn’t think of himself as a small man.

There was a pause after Vecco finished telling his story which Jean-Michel François assumed was meant for his own. But before he could begin, Vecco glanced down at his watch. “Shit. Starting up again soon. You're staying here, right? I'm down the street. The Hyatt. Come by and look me up after,” handed him a card and rushed off.

The rest of the conference went by unremarkably. Jean-Michel François gave his presentation (“Better cross-force information sharing through request templates”) and was pleased with what he thought was a robust round of applause.

At the end of the day, waiting for the elevator with other conference guests, all of them going through the cards they had collected, he came across Vecco's. They hadn’t run into each other in any of the talks or break-out rooms. He’d almost forgotten that they’d met.

The elevator came. The crowd shuffled in before him chatting to itself: “It was very good, that last working group.” “Oh, yes. Very productive.” “What are your action items?” “Well—”

What time was it? Eleven past eight. He looked at the card one more time. When the elevator doors closed, he was not inside.

The Hyatt turned out not to be ‘down the street,’ or else Jean-Michel François had misunderstood, so it was already after nine when he arrived. The front desk said Vecco would be down shortly. CNN international was muted on the television. On the chyron was written:

JOINT PROCUREMENT DECISION EXPECTED SHORTLY AS EUROPEAN COUNCIL MEETS

“John, sorry to keep you.” Vecco’s suit jacket was gone, and in a shirt one could see how swollen from muscle his body really was. “Hope you weren't waiting too long?”

“Ten, maybe fifteen minutes—”

“Fantastic,” Vecco nodded. “You up for a beer?”

It took them another half hour to find somewhere; Vecco wasn’t sold on the cafés; “I like a real bar, you know what I mean?” Eventually they settled on something called McGinty’s. The noise inside was deafening.

Vecco came back to their table with two tall black glasses. “Guinness,” he shouted. “I always drink Guinness in an Irish bar. Cheers.”

“Thank you,” Jean-Michel François shouted back, and flinched a bit at the taste.

Each of the televisions behind the bar showed a different sport: soccer, tennis, basketball. Vecco pointed to this last one. “Don't recognize the teams,” he shouted. “These European?”

“I do not know very well basket,” said Jean-Michel François; then, remembering, added: “Ball.”

“Love it myself. Played in college. Bad knee, though. FBI does a tournament every year, so I still get my hand in every now and again.”

“That is interesting,” said Jean-Michel François. “You do sport at the FBI? In the French police we don’t do this. You have time with all these big cases?”

“Oh, you gotta get some down time, brother. Besides, it builds teamwork, trust. And trust is the name of the game. Gotta know who you can and can’t believe.”

“Yes. Like in this movie, with DiCaprio. I don’t know it in English.” The back of his hand touched Vecco’s bicep: like the ball at the end of a banister. “It’s like, one policeman, he has this important case, and the other, who is supposed to help him, he is working for the enemy….”

“Doesn’t ring a bell. Me, I’m old-school though: Stallone, Schwarzenegger. Good guy, bad guy. Black hat—”

“White hat.”

“Bingo.”

“It is a good movie. You should try to watch it.”

“Will do, will do.”

An advertisement had come on: white sand beaches, a couple hiking a volcano, a black boy and a white one laughing arms over one another’s shoulders. JP Morgan had a new checking account.

Both men sipped their beers.

“So what’s it you do over in the— It was French police, right?”

“Yes. Police nationale. National police. It is kind of like your FBI. I do—,” he tried thinking of the English word, “—liaisons. International cooperation. If you have ever made a request for information, it was us who handled it.”

“That right?” Vecco nodded over the rim of his glass. His eyes had descended from the screen to the level of the behind of the girl in front of them at the bar. "Funny you mention it, John. I might have. Pierre Choucair? That name mean anything to you?”

“No.”

“We asked you for some info on him maybe a month back. Was hoping you had your own investigation going. Surprised you didn’t, really—” Vecco stopped. “I mean, I probably shouldn't say anything.”

Jean-Michel François tilted his chin to one side as if to say, Probably, probably.

“But it is an interesting case—off the record here, of course, but we’ve got this guy Choucair taking money from some bad dudes. Russian dudes.” Vecco paused for a long-sighted stare. “It’s a network. We’re still trying to piece it together. Choucair’s a piece, maybe a big piece. But we’re missing something.”

The American’s eye had a certain, saffron-colored light in it, perhaps from the Estrella sign. He leaned in close enough to speak without his usual boom. “Don’t tell anyone I told you, John, but if you look at where this guy is, what he’s doing—”

Then he pulled back abruptly. “But listen to me, all this shop talk.” He snapped his fingers at the bartender and let them linger for the girl at the bar when she turned to look. “We had that bullshit all day. Let’s get hammered.”

Warmed by the otherwise disgusting drink, disposing him to almost any idea even if barely articulated, Jean-Michel François said, “Why not?”

Vecco bought them another Guinness, then another. The third time it came with a little glass of Baileys that Vecco told him to drop into the beer. Foam surged instantly towards the rim of the glass; “Down it!” Vecco cried, whereupon Jean-Michel François discovered that there was whiskey lurking at the bottom too.

Within five minutes he felt as if he’d drunk from a fire extinguisher. He left Vecco at the bar talking to the girl. And she was a girl: twenty, a student, probably, he didn’t actually know if he’d heard her say her name. Françoise, Frederika. Something.

The point was that they were not much interested him, and that he was unpleasantly drunk. But then right as he was making his excuses to leave, Vecco seized his shoulder with the force of a bear. His plump cheeks shone with feeling. “John, brother. It was great to meet you. And seriously—if you get into this guy—reach out to me.” He patted himself on the stomach. “My gut’s saying don’t trust this guy. And my gut’s never done me wrong before.”

Jean-Michel François wanted to concur, but Vecco had already returned to Françoise. To the girl. Not Françoise; he was François. Frederika.

As he came out of the bar, Jean-Michel François realized how far he was from a bathroom that he could use with dignity. When the urge came, he peed on a phone box mummified by stickers for movers and call girls. An old woman walking a little cotton swab of a dog said something in a tone of reproach, but he couldn’t hear her and wasn’t listening anyway.

Checking out the next day, head like burnt molasses, the receptionist passed a small, unmarked envelope over the counter to him. “Someone dropped it off for you this morning,” she said, with a strong Flemish accent. “An American, I would say.”

“How did you know he was American?” he asked.

“Oh, it's the fat face.”

He pocketed the envelope and strode off. He was already late for the train and not sure he might not have to stop somewhere to throw up.

His carriage was somewhat crowded but he did manage to have a right-facing seat. He emptied the envelope onto his tray table: out came a lone USB key. Outside went the three-tones of the Belgian countryside, wet white, wet brown, wet green, interrupted momentarily by the cedar brick of the border crossing, which then gave way to France with its own whites, browns, and wet greens.

Jean-Michel François wasn’t paying attention to any of it. He’d begun opening things.

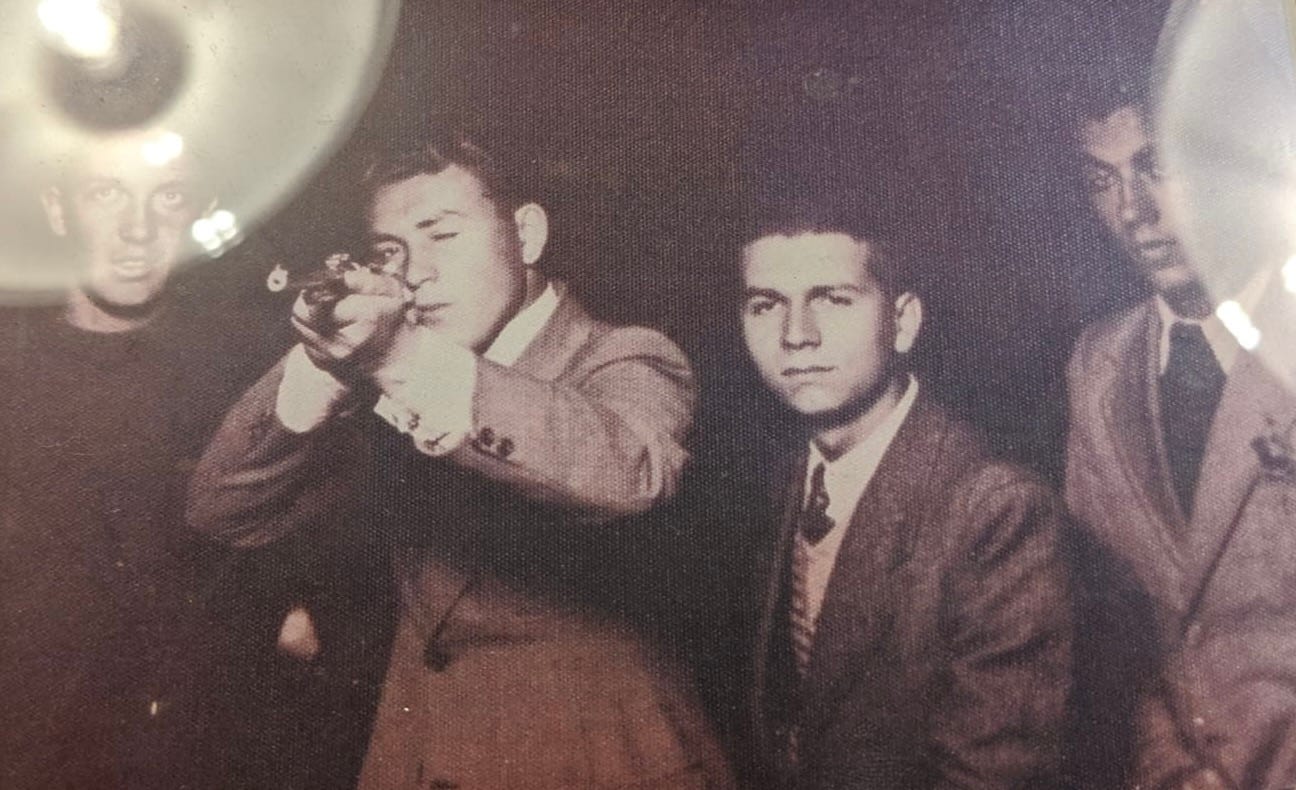

The first was a series of jpegs: A photo of a three men in a garden with the tallest one circled; this same man next to a woman in big sunglasses, him smiling, not her, four children lined up in front, all of them posing by a statue in a European square somewhere; at a convention booth now with his arms over two very young women in those one-pieces cut to show the line between groin and thigh, the word NANTEX printed on the false wall behind; and then a headshot, probably LinkedIn from the red knot of his tie.

He had a sharp face, that was in the bones, but up close he was puffy and pallid; his skin had a sheen to it that didn’t look like it would come off with a towel.

Next were bank statements. An English bank. Dozens of outgoings and incomings: out to a few different French IBANs, in from—he didn’t know all the codes, but he saw Cyprus, that he recognized. And this one: Poland?

“No, look. I’m on the train,” the man in the seat in front of him was saying in French. “So obviously—yes, yes, when I get back. But look—under-over, I think it’s finished. Yes, they’re leaning back domestic. Yes—she caved. Got her in a vice—well, you know I can’t—no, but we can speculate—whatever deal she cut for them in the first place— Exactly. Nothing’s free.”

Amounts all over the place. Coded references. He tried to understand, to see some pattern, but his head floated, adrift in a poisoned Sargasso.

He closed the screen. Rain raking the windows from an oil-slick sky. He considered the night before, but hardly had he been in his head a moment before the ache that had been hiding down in the deep seized him by the foot and pulled.

He rolled his cheek against the nub of third-class cushion. “The Americans?” said the voice as Jean-Michel François surrendered to an ungracious sleep. “I mean, they’re going to shit a brick. God knows what they’ll try to do.”

At five o'clock traffic on the Péripherique was already bad, but he had the hand-strobe going on the roof so no one dared enter his lane, and he was making good time.

Lucie was at the gate waiting for him when he arrived. As soon as she saw him, she punched the boy next to her and ran up to the car, leaving the other children watching enviously as the blue light spun round and round.

Lucie exhaled onto her window and wrote something on the fast-vanishing fog. “I got 16/20 for the English test. That was the highest grade except for Charlotte,” she said.

“That’s impressive,” agreed Jean-Michel François.

“But Charlotte’s mother is American or something. She’s from—Adelaide. That’s in America, right?”

“I think so. Yes.”

“Is Cécile coming over tonight?”

“Yes.”

“Is Bertrand?”

The car filled with a run on the digital xylophone: a +1 number on the dash display. “Hold on. I have to take this. Hello?”

“Johnny, Johnny,” Vecco thundered. Jean-Michel François punched down the volume. “Long time no see.”

Here the boulevard abutted a bad suburb: stained concrete towers, clothes drying on colored balconies with the brightness of old newsprint. He’d given Vecco his number? “Hello, Vecco. Yes. It is good to hear from you also.”

“Just wanted to check in, see how things were, if you got a chance to read what I sent?”

“Yes, actually, I have read it.”

“What do you think?”

He dipped right for a delivery scooter; enough time to realize he did not know. “I think it is something, yes.”

“Funky, right? I mean, he’s an engineer. He’s got an English account, okay, but what kind of business is he doing in Cyprus? Or Bulgaria?”

Lucie, chin on one palm, had begun tapping the window with the finger of the other. Jean-Michel François said, “It is as you say, funky.”

“Anyway, just thought I’d pass it on your way if he ever gets on your radar. One cop to another.”

“I understand. Yes, this is very helpful. Yes, I thank you. Thank you.”

“No problem at all, Johnny. No problem. At. All. And hey— The FBI really appreciates you. You know we remember our friends. Alright? Alright. You have a great day now, Johnny. Take care.”

Vecco hung up. His daughter said: “It’s ‘helpful’, dad.”

“What?”

“You said ‘elpful’. There’s an aitch. Helpful. Also, you didn’t answer: Is Bertrand coming?”

“He is.”

She stuck her lower lip out at all the ugliness passing by. “I don’t like Bertrand. He’s— unhappy.”

She stayed to greet her aunt when she arrived, but went up to her room immediately after and didn’t come down again.

Céline’s smile as she and Jean-Michel François did the bise: pinned to either side of her face. A little lost girl in a department store, staring at everyone as if waiting for them to turn into her mother.

Then, Bertrand— The ghost at the feast, hunched over in his rumpled sweater and porthole frames. He hardly said a word at the apéro, not until his third glass. But after it the fourth came a little quicker, and the fifth even quicker; and so did the realization that he did in fact have plenty to say.

By dinner, they were three bottles in, Camille not drinking, and Céline still nursing her first glass, though Jean-Michel François, between them with Bertrand dead ahead, was doing his best not to be sober.

“This is starting to sound a little like conspiracy talk, Bertrand,” he joked, but only a little.

If eyes had ever gleamed, Bertrand’s did. “Conspiracy, conspiracy. Everything’s a conspiracy. You ever read the news? A pound of butter’s 2 bucks yesterday, 4 today. You think that’s just God or bad luck? Please.”

“I don’t know—,” Céline spoke without looking at her husband, “—it’s all very complicated.”

“It isn’t complicated. It’s simple: some people are fucking, and some people are getting fucked. Now which ones are we?”

Jean-Michel François made a deliberate attempt at laughter. “At least everyone’s having a good time.” Céline offered a wan smile, but Camille was a wall.

“Take the elections,” Bertrand said, ignoring them. “How is it every time? ‘The republic’s in danger! We have to vote to save it—whatever the cost!’ And that’s not conspiracy. Come on, we know how it goes. How do you make someone look reasonable? Stick them between a liar and a half-wit.

“So we get, on the left—,” dangling a limp wrist, “—someone feckless, corrupt, a weak narcissist, slave to his own appetites, chiefly, the adoration of the crowd.”

Jean-Michel François glanced down; Cécile’s fingers over the threshold of his place mat.

“And then, on the right—” Bertrand’s wrist straightened, his hand a claw. “A raving lunatic, spitting on all wisdom, sneering at all shibboleths, no matter how heinous the contrary position may be: ‘And what harm did Vichy do really? When we look at rural incomes alone in the year 1943….’”

Bertrand held out his glass for a refill; Jean-Michel François obliged, but only to attend to his own after. “Like that anyone, no matter how ruthless, megalomanical, how driven by their hatred of lives not their own, can end up being the only sensible choice. Voilà: Madame Our Courageous President.”

Camille frowned. It was not something she did often—not something she had cause to do—and the fact that she had to now did not sit well with her. “Frankly, Bertrand, I think it’s deeply disrespectful to everyone who voted for the president to suggest that they were manipulated.”

“Disrespectful? To those black shirts? Pardon me. Ten years ago that woman was the devil herself, a Manchurian Candidate, stooge of foreign strongmen. Today she’s raising a glass to good old Jean Monnet in Luxembourg Square. Joint army, joint budget: there’s nothing she isn’t for! And you know what they call her in the press? ‘A true stateswoman.’ Degaulle reborn.”

“I don’t think anyone voted for her because they believed we would leave Europe, Bertrand,” said Camille.

“Despite her having said so.”

“Her views have evolved, but they had to. Look at the world situation right now. In Europe we’re surrounded by hostile nations. France can hardly afford to alienate its partners when we need them most.”

“And if we sell the hospitals to the Americans and put the Arabs in jail on the way, so be it. Everyone’s been waiting for someone to do it anyway.”

“Now that’s just outrageous—"

“Besides, the hospitals,” Bertrand went on, “I mean, of course, look at the state of them! They all say when they get into office, Left, Right, Green, Fascist: ‘We wish we could, but it turns out there isn’t any money.’”

“But do you know what—,” what was faintly mocking in his smile turned almost imperceptibly to fascination, “—the nuclear arsenal, now, that takes courage. You have to be a committed cynic to go so far. Even the Énarques didn’t dare. And yet nobody bats an eye when she puts our national defense on the street like some African shopping Chinese whores on the Boulevard de Belleville.”

Bertrand brought his glass to his lips as if to drink. “Except that she’s no pimp,” he said instead. “She hasn’t got the stomach for it. She’s just a whore. A frantic, filthy little whore.” And he downed his wine in one.

Nobody would have missed the look he’d given Cécile even if he hadn’t let it linger. It was the first one of the evening.

The wine was done. Jean-Michel François would’ve been very happy to get up and get more, but Camille stood up, and he saw on her forehead the little vee.

“I think it’s time for dessert,” she said.

Bertrand stared at her from the corners of his eyes down which the lids had come halfway. “You know, Camille, I could almost believe you voted for her.”

There was a long silence. Then Camille, looking straight at him, said: “I did.”

Cécile staring at her half-eaten food; Bertrand about to drink from habit, unaware that he was empty.

Jean-Michel François stood up. “We have your almond cake, Cécile, that’s right? Maybe we can eat it in the garden. It’s a warm evening.”

Outside the light though still gold had peaked and was on the descent of a gradient that ended in silver. He zipped up his coat and stared between the hedges that hid them from the street, over the gate, at the lights flickering behind the curtains in the window of the house across. Cécile was warming the cake and would bring it out after. Camille had gone upstairs to check on Lucie.

The door clicked behind him. He knew it was Bertrand without turning from his shuffle.

Staying a bit, he offered Jean-Michel François a cigarette knowing it would be refused. He shrugged, lit his own, and took a very long drag.

After a long silence, he said, “Jean-Michel, tell me—” He took another drag, eyes on the night. “Did you—”

“Vote for her?” Jean-Michel asked. “No.”

He hadn’t—the first time, for the simple reason that someone else had been the president. The second time it was her, so he voted for her. He was sensible: he supported whoever was in government, so long as it wasn’t the socialists.

Up and down went the lever-action of Bernard’s smoking arm.

Bing. Jean-Michel François’s phone. He clicked it on, clicked it off, came up with a frown. “Sorry. New, um— New case. Started on trip to Brussels last week. Interesting—banking stuff—with the FBI, actually.”

Bertrand, eyes trembling as if from the exertion of sight, looked like a man woken from a dream by someone calling to him in foreign tongue. “I hate Americans,” he sighed, then crushed his cigarette under his heel and went back in.

They ate the cake quietly and quickly. When it was time for them to go, Bertrand put on his coat and walked out the door without saying goodbye.

Cécile smelling intensely of cigarettes. Jean-Michel François kept a bit back from her for the bise.

That night the sex was blunter and more vigorous than usual—like with animals. It had been an unpleasant evening, he thought lying on his side after, but it had been worth it at least. Still, his gut felt like he’d eaten or drunk something off, and he stayed awake for hours waiting for the feeling of feeling good.

“Come in, Jean-Michel,” the commandant said. He’d been on holiday and his white hair was all the whiter against a deep tan.

They sat down, Jean-Michel François hands in lap, right leg over left, the commandant turned sideways towards a cartoonish painting of boys walking to school on a village thoroughfare.

“No decision has been made yet,” said Delestrez, “but, look: I thought that I should be frank with you. I spoke with Lemaître yesterday—it’s down to two. But as it stands—the other one, you see, it’s a woman. And it would be the first one—”

Jean-Michel François opened his mouth, waited for something to come, waited too long, closed it.

Delestrez tilted his head to the left, disappearing behind the white of his hair. “You understand that these days, these things, they are very political. I’m not going to say that I feel this way myself, but you know, with the president— It’s well-seen.”

Very slowly, as if swallowing each time, Jean-Michel François nodded.

The commandant’s head flipped right: now he was a puffy, shaven chin. “You see, it’s not like in the past. In the past,” he sighed, “what was well-seen was: Did a man believe in the organization? Was he loyal to his colleagues, to the police? If he was, and he had a bit of brains and didn’t show off, he would move up. Because one knew where he stood.”

“But it’s different now. And maybe, I don’t know, it’s better. Perhaps we had too parochial an idea of ourselves? Today what counts is: Who ? I don’t mean who here. I mean—” Out swept both hands. “Europe. America. This is how it is now.” He leaned back in his chair and sighed, head shaking, resigned to sin in a sinful world. “Is it good? I don’t know. But all the same it must be. We French, maybe after all we are too small, too weak. We must swim with the sea.”

When they shook hands at the door, there was a certain softness in the older man’s grip. “Of course, this was between friends. And nothing’s sure yet.”

“Of course.”

He was about to go when the commandant said: “Oh, I’ve been meaning to ask: what happened with that file, from the FBI? Did we have anything?”

“Nothing.” Then Jean-Michel François added: “But I looked into him a little. Some curious money. From the east. But I haven’t got time for a real investigation.”

Delestrez nodded absently; such was the way of things. “If you need time, take it. It’s the Americans. It’s not good to disappoint them.”

Back at his desk, he sat, slouched in his chair, bathing in the drone of the office without himself getting wet.

Ding. This time, he didn’t bother.

Ding.

Abruptly, he dragged himself up to his computer, double-clicked National Police; Case History, Create New, Generate file number; inquiry active, subject: CHOUCHAIR, PIERRE.

Then he closed down his computer, signed out as sick, avoided anyone who tried to talk to him, and drove himself home.

He called Vecco from the car. It went straight to voicemail. “Vecco,” he said in the absent cadence of the driver, “hey man, I just want to let you know that the case— It’s good, it is happening, I am hoping we can have some good result soon. Okay? Okay so good. See you later.”

The radio coming back in after he’d hung up: “…Dassault shares soared on word that it had won a ten-year, 30-billion-euro MoD bid to build France’s first fleet of intercontinental ballistic missiles with partners Thales and Nantex-Marechal….”

He scrolled away looking for music but stayed only a second on each station that was playing any, until at last he turned the whole thing off and drove the rest of the way in silence and the pebble dash of afternoon traffic.

Jean-Michel François gave the soil on either side of the front door a last spray with the hose. This year, Camille had decided that they would plant irises. But he was truant clearing the beds and getting the seeds in the ground. Now it was already Spring and the house was marooned behind a moat of bare, boggish earth.

He went to the back of the house. Lucie doing cartwheels in the grass. Cécile was at the patio table facing her. She was hunched over one knee so her elbow could sit on it; the same hand held a cigarette up that was half-burnt already, perhaps forgotten. She was in her bath robe; she’d been in it all week; he hoped it was closed this time, or if not, that she had remembered to put on underwear.

Camille was in the kitchen. He slid the patio door open as quietly as he could and went in, then inched it back closed.

“Still no shoots,” he said. “I hope the seeds weren’t bad.”

Camille was emptying the dishwasher. “The seeds are fine. It’s just late, that’s all.”

Jean-Michel François poured himself a glass of water from the filter in the fridge. Through the window, he noticed that Cécile had gone. “Has she said anything about—about arrangements? With Bertrand?” he asked.

Camille shook her head. “He’s not answering any of her calls.”

“Right.”

His phone began vibrating. He took it out. “I’ve got to take this.”

“John.”

“Hello, Vecco,” said Jean-Michel François, crossing the lawn to the far side of the garden. “How are you?”

“I’m in Paris, John, and I’m wondering—I know it’s Sunday, but: are you free?”

He toed a fresh hole in earth. “Ah, you know, I would, eh, normally I would be. But tonight I am with my family. The sister of my wife—”

“I wouldn’t bother you on a Sunday, John.” Vecco’s voice was uncharacteristically even. “It’s just that there’s something here you’re going to want to come out for.”

He turned back to the kitchen. Camille was at the dining table with Cécile, staring at the ground.

“It’s Choucair, John. I looked at what you gave me, and I’m pretty sure whatever he’s getting that money for is happening tonight.”

Suddenly Cécile’s face crumpled, then body; she collapsed onto her palms, sobbing.

“Vecco, okay, but I am not, you know, even working—”

“I get that, John. Nothing cowboy about this. I’m not even involved. But you’ve got jurisdiction on this one, right? He’s an open subject? And you’ve just gotten an anonymous report of suspicious behavior. Sounds like it’d be smart to follow up on.”

Camille held her sister’s arm as paroxysms of anguish wrenched her to-and-fro, then lunged for the other when she began to beat herself viciously round the head.

“I mean, this guy’s doing aerospace for one of your biggest defense contractors. And he’s got money coming in from all the wrong addresses. You’re not worried?”

Cécile crumpled into her sister’s lap. He couldn’t see her face, but her shoulders moved in a way that suggested she was speaking. Then she held something up: her phone. Camille took it from her.

“But look, I get it— It’s kind of crazy. I just thought— Hell, why not—"

Suddenly Camille lunged back from her chair, knocking it over and sending her sister falling to the floor. Even through the double-glaze, he heard the anguish in Cécile’s wail.

“Just tell me where,” said Jean-Michel François, already heading for the driveway. “I will come now.”

“Shit. Shit! Fantastic, Johnny. That’s just fantastic. Here—” Vecco read him off an address near Parc Monceau. “Oh, shirt with a collar. And nice shoes.”

The feeling that John-Michel François had as he walked to his car was one of extraordinary lightness, as if he were without substance, no longer anchored in the world; that if he blinked, he might disappear.

The lights came on when he started the car, and Lucie appeared.

He rolled down his window. “Lucie, what are you doing?”

“Where are you going, daddy?”

“Work, sweetheart. Last-minute thing.”

She frowned—and for the first time he noticed: that same vee. “Are you going to be back tonight?”

“I—”

He couldn’t look at her. “I hope so, Lucie. I do,” he said, substituting an ineffectual smile.

He backed out with her watching him until the turn onto the cul-de-sac plunged her and the yard into the dark. Then he drove down the road to the crossing with the Carrefour Mini where the light was red.

Waiting, he began writing to Camille from the car: EMERGENCY. WORK. NOT SURE YET— Then he saw the three dots in the bubble bouncing and shut off his screen.

The light had still not changed. He was alone but for the streetlamps and the long shadows they cast over the shuttered streets.

He punched the glove box, got out the strobe and fixed it to the dash, hung a left onto the ramp to the Péripherique, and took off towards the fatuous daylight of Paris, threading his way through the suburban night, a skipping stitch of carbon blue.